In the Dark Light of Currency: Everyone Reviewing Each Other’s Books

Kelly Clare, Demonstration Forest, Community Mausoleum, April 2025, 37 Pages

Maxwell Gontarek, Study for Swimming Hole, Community Mausoleum, July 2025, 68 Pages

Eric Wallgren, Icewalker & Dirtworm, Community Mausoleum, October 2024, 27 Pages

Jon Conley, Deadheading, Community Mausoleum, September 2025, 60 Pages

Hilary Plum, Important Groups, Community Mausoleum, January 2025, 46 Pages

Community Mausoleum has been publishing books for a little over a year now, and in the mode of self-eval, taking stock, or otherwise memorializing that publication activity, I thought it might be cool to have the press’s current authors all review each other’s books. I thought it would be especially cool to have them do it one big pile, each of them writing separately with minimal parameters, and then I’d assemble whatever came in in whatever form could be made to make sense on a page of HTML and Cascading Style Sheet.

I reached out, not that long ago, not expecting much, ready for this idea to fail, and then they just did it, quickly and generously and well. To my surprise, I was surprised by this. Not because of the quality of their attention and writing and the time they took for each other, but because the book review, which I’ve spent a lot of time around and think a lot about and know to be an excitingly limitless form as well as this puzzling kind of currency in certain contexts, can seem so heavy and fraught at times—the stakes feel high, in the dark light of currency, with criticism another exposure of one’s self after all, and in the runoff market of ideas and jobs and hustles and rushes to publish one can worry what gaunt-looking professional cloud hangs over the whole practice, or else the sour scent of a suspicious social economy. Which doesn’t really make sense, because there’s no evidence of those stakes being very actual. No one gets promoted or buys a book because of a review. You can make friends, but no one reads reviews. No one reads books. No one reads anything. Right? What are we doing here.

These reviews weren’t written for money or bylines. Who’s going to read them? They were written for each other and for you. They are reminders and evidence not only of what’s possible and maybe even hopeful still in the deep gears of our micro-cultural discourse jalopy, if we want that, but specifically that the work of book reviewing, especially in a small press context—down here, buddy!—is not a professional activity. It’s something we do for each other. It doesn’t have to be exceedingly hard or formal or serious. You can just write some cool thoughts about a book you liked and have a good time with it. Which, if I may be permitted to cast a single publishing wish down the rotten well of this new year, I’d like to see a whole lot more of: Everyone reviewing each other’s books. It’s not going to get us paid. It doesn’t matter anyway. It matters a lot more than that.

ZP

..

Kelly Clare, Author of Demonstration Forest

On Study for Swimming Hole by Maxwell Gontarek

These are such humid poems. Muggy water that presses in, goes up your nose. Poems full of mold’s density and mulchy promise. While inside Maxwell Gontarek’s Study for Swimming Hole, I feel like I’m hovering one inch away from the filmy reflection, always.

I have thrown myself into many swimming holes over the years, found the muck afterwards trying not just to adhere, but to press in. “This is how music works too,” Gontarek writes, “The scurry under the nails / our residual / green shell would ease / into clear fold if we could hear it / The cream under the carpet / and in our ears / small moving hairs.” In the muddy ear, distance is impossible.

The illusion of distance, the invention of linear perspective, is the lowest point in art history. A professor of mine decades ago wouldn’t drop this belief. There’s nothing real in a replicated palazzo made of receding lines. It’s just rows of smaller and smaller trees. As in Study for Swimming Hole, linear perspective isn’t possible when you’re in the world, stepping on the world, shoving the world into your face, throwing your limbs deeper into it. The world is crammed. Arm’s length “nature poetry,” like those Bierstadt western landscape paintings where our perspective hovers higher than any human view, pushes us away from the “nature is metal” Annie Dillard-ness of it all. “Right now” is too itchy and too close.

But what of the depiction of the real thing? How can we see it? While reading Study for Swimming Hole, I kept underlining every moment with the word “real,” starting with “Rotting in a curt whorl/Realism inverted is use.” An inversion involves placing something upside-down or inside out. It is not necessarily a negation. Realism inverted, like a tarot card, becomes action in “use.” To grasp, to handle, to rot as matter turning over, to become nonhuman microbiotic usefulness. Press in and hold on.

Capital “R” Realism in art is a term coined in the 1840s. Realism discards pageantry and wealth and instead embraces frankness and grit and labor. Realism is direct. If you’re really conducting “a study,” the observed world is brash and confusing and makes, as Gontarek writes, “impossible any “outside.”” The density in Study for Swimming Hole, where “the tropic of reality lags / its tide of eyes” and “the landscape can open with impunity / and allow a body to pass through,” is Realism. As Gontarek pulls from a varied collage of sources, we break the surface of found language and found world. We breathe in the distortion of a haze, a reflection in water, fog hung with mineral vapor.

“The object is encrusted in the object,” he writes. Yes, I agree. Doubled, and with a penumbra.

..

Maxwell Gontarek, Author of Study for Swimming Hole

On Demonstration Forest by Kelly Clare

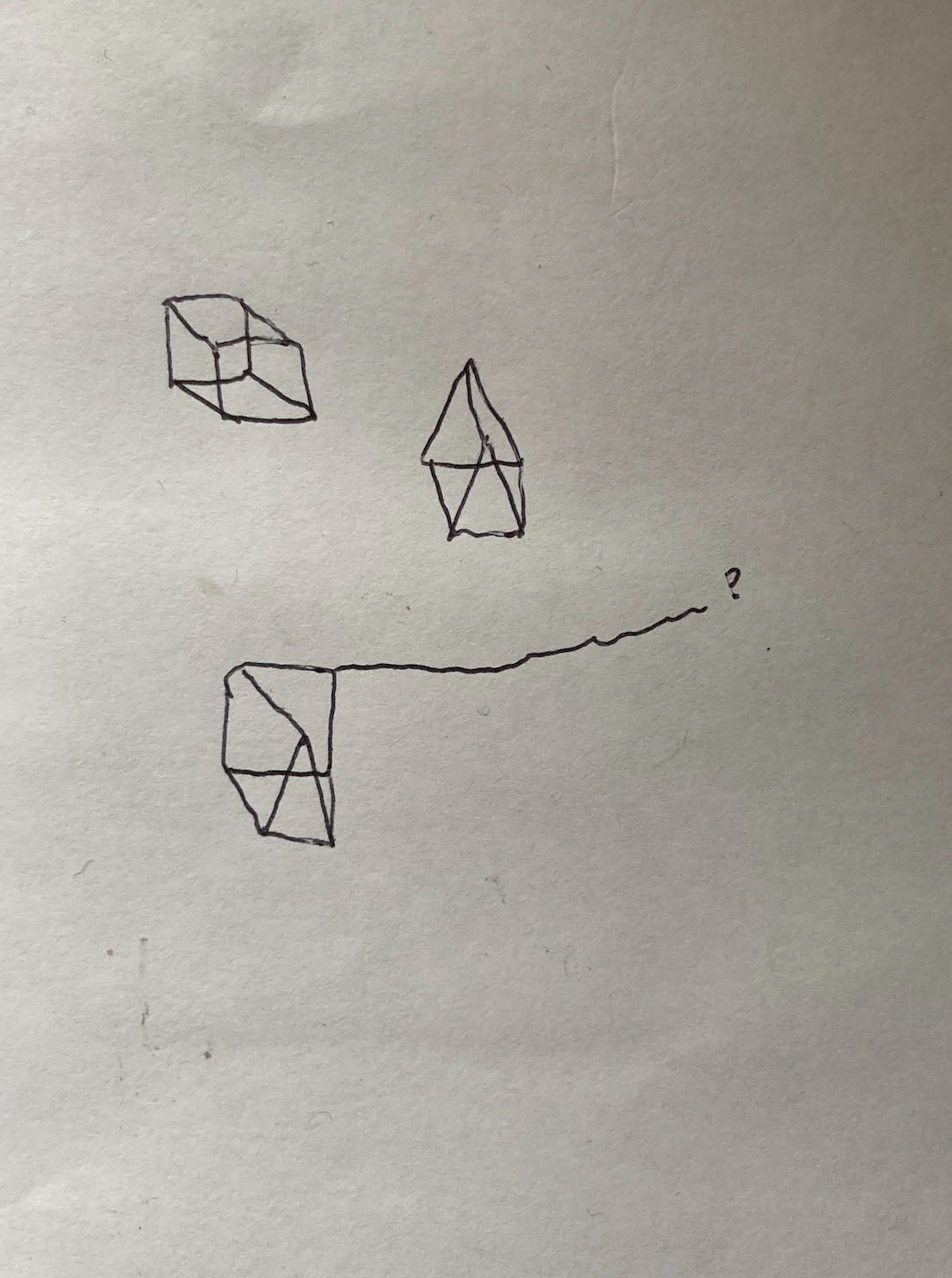

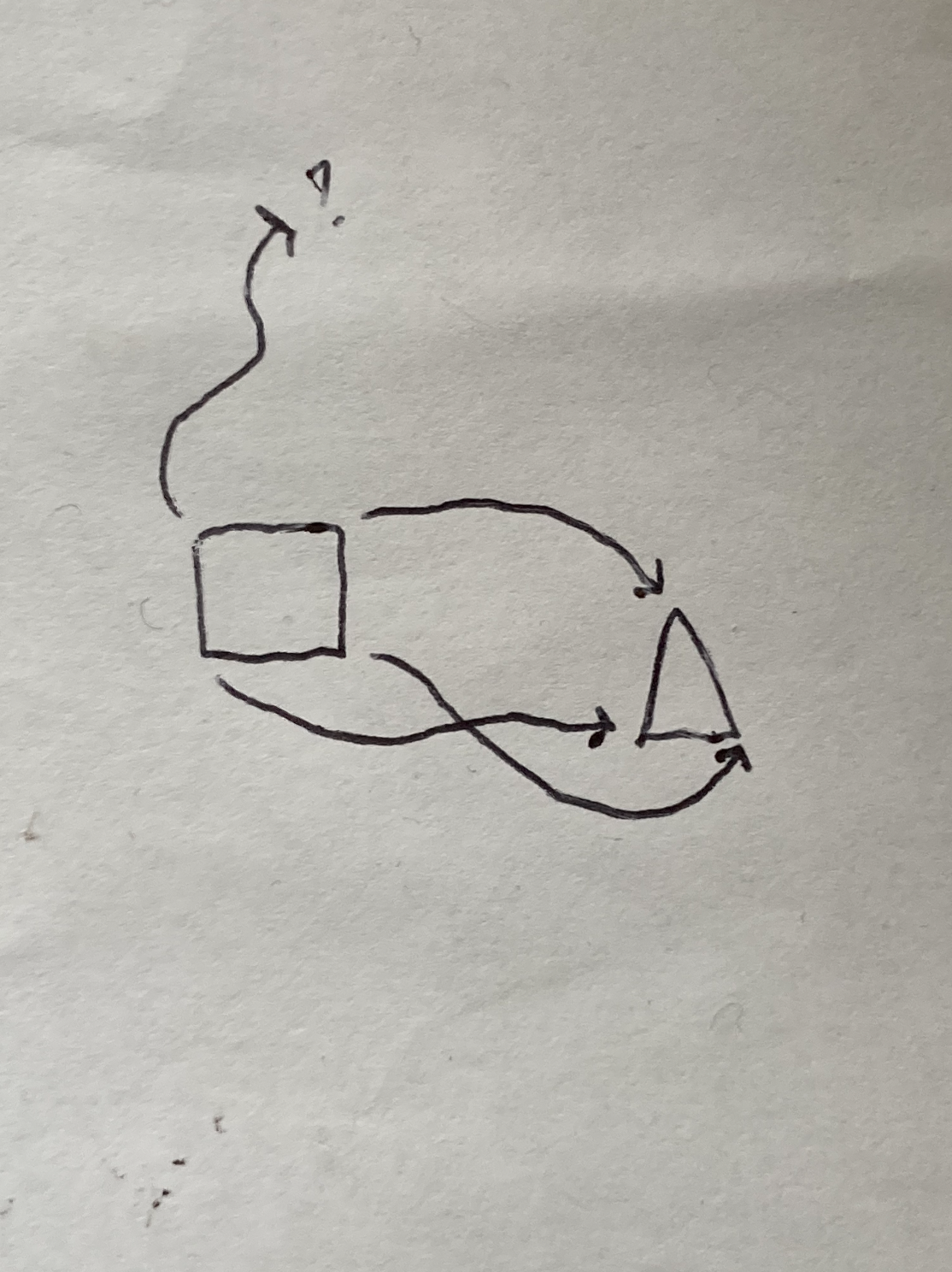

1. Tried drawing a diagram to explain a feeling about this book. To draw a 3-D square you draw 2 squares and map the corners of one onto the other. To draw a 3-D triangle, ditto but with 2 triangles. This book is like a 3-D object that begins with a square (“the book”) and a triangle (“this book”). It maps 3 corners of the square onto the triangle, but there’s one corner that’s left floating, somewhere dimensionless. By mapping a square (i.e., “the book,” and all its expected functions, and all the desires you bring to bear on those expected functions) onto a triangle, you get this feeling, reading, that those functions and desires are going haywire, should go haywire, and that when a corner, or stake, of “the book” is dispensed with, other stakes become possible. “This triangle is not a field of study” because the “field” in this weird third-D allows space for lines––of poetry, inquiry, latitude, longitude––to be written which could not be written in “the book.” “The wires exit the house. / The wires exit the house some more.”

2. Haywire as ethernet.

3. It follows that no book should be the same shape as any other.

4. Revisited Hito Steyerl’s “How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File.” Especially the calibration targets in the desert.

5. Demonstration > Installation.

6. How literal-sounding notation accrues nonliteral-sounding meaning but then that meaning becomes literal again.

7. How “the moldy screen / goes both ways” and how this book links forest networks and computer networks, woods and word-processors, bites and bytes, blurring LAN.

On Important Groups by Hilary Plum

1. In Tomatoes + Why Doesn’t the Far Left Read Literature?, Nathalie Quintane writes that we need more “living books” today, or books which “include in the text the entire hors-texte, which it opens out onto and which makes its outline legible.” If any book in recent memory includes in its text the entire hors-texte, it’s Important Groups, which opens out onto what seems like the entirety of recent memory, making its outline more legible than is normally possible in the middle of all the devastations and mollifications doled out by the status quo.

2. How a long poem can have a linear-feeling thrust/lilt but one that keeps doubling back on itself, concentrically. How this renders the way lives are not points on a line “forward” (a line constantly amputated by neoliberalism, neocolonialism, etc.) but really more like little momentous centers undulating in waves of overlaps.

3. The line as jut.

4. How a voice can be one voice and feel dialogical. How it’s not surprised. Quintane: “The fact that people are taken in by a language that stages itself as a spectacle to itself … is perhaps one of the signs that those who read still expect no more from a revolt or political rupture than a spectacle, and not a liberation. If they really wanted to be more free, they would expect books in other languages, not necessarily more inventive ones, but at least more ambivalent ones.” Ambivalence here not meaning “on the fence,” but like an actually liberatory poetics that’s informed by juts, that doesn’t couch itself in a poetics of liberating you, the reader.

5. Scalar shifts like “you can hear this inhuman vibration / it’s just on YouTube.”

6. Revisited Aisha Sabatini Sloan’s “A Clear Presence” and thought about this formal thing shared by poetry and essays, a kind of hither-and-thither-ing between a clear (evident/direct) presence and a clear (transparent/ambient) presence. How they both make visible something about their material which it is orthodoxy’s purpose to keep invisible.

On Deadheading by Jon Conley

1. There is the entire history of the world in the unsubstantiated etymological kinship of “privatized / & ivied.”

2. There is the entire history of the world in the dissonant a sound in the line “resembling, reassembling.”

3. Lyn Hejinian, writing about the tendency of words to attract themselves to other words, writes: “It is relevant that the exchanges are incompletely reciprocal.”

4. How the phonemes in the opening poem, “(forest),” form a kind of electrical-treeing of rhyme/hum, where “name” attracts “strange,” “away” attracts “layers,” “canker” attracts “cherry,” and a line like “Lo river low / Glade & grove” stretches its vowel drone through a parallel pattern of processual l, r, and v sounds.

5. Unlawful glissando.

6. How English can be made to not feel like English in the mouth, as in “To oyamel fir,” “their unworn / who,” “lime glade film,” “least bittern,” “Lust selenic pink faun,” and “soak ellipt.”

7. What is place, what is ink, what is plaque.

8. Imagined some language philosopher repeating the line “The river is rather” over and over, uncontrollably, and then trying to put their fist in their mouth to stop it.

9. The line “The river is rather” lead me to a Wikipedia page on hydronyms, where a section marked “insufficiently detailed” lead me to believe that the word “river” came from the word “rather.”

10. Or maybe it was the other way around.

On Icewalker & Dirtworm by Eric Wallgren

1. Heurtebise leading Orphée through the mirror water. Red rubber gloves and “bees in a hive of glass.”

2. Mandelstam taking an axe to the reflection of the stars in a trough of frozen water and “the magnetic pull / that Icewalker follows, / dissipating / into freckles: different stars / dotted across the sky / and the different icewalkers / that follow them.”

3. How we used to share one spherical body, with 4 legs, 4 arms, and 2 heads. “A mess of confusion / that pulls feather / after feather / every direction outward / and then untangles into / a sharper, / clearer tunnel.”

4. Your cosmogony is growing over my fence, so I’m allowed to cut it down. Your cosmogony is double-parked, blocking traffic. Your cosmogony is too loud. Your cosmogony is leaking.

5. Interior ethnopoetics.

6. Heriberto Yépez: “Ethnopoetics as: a strategy to leave behind ‘ethnopoetics’ as a curious branch (60’s related) of literature and make it inseparable from poetics, until the term is useless for being so obvious and fancy.”

7. Space-wolf, Mr. Cogito, and noone.

8. “The wasted future / curls its finger / in a ‘come here’ motion. Not shackled / nor enlivened by possibility, / but shackled and enlivened / in an entirely new way––in fire, / in obliteration, / a burning / both focused and entropic / that crackles into small pieces / which hold / precariously together.” A book about how to hold together the category of “precariously.”

..

Eric Wallgren, Author of Icewalker & Dirtworm

On Important Groups by Hilary Plum

It should come as no big revelation to anyone who’s been paying attention at any point in the last, I don’t know, 250 years, that the U.S. is and always has been largely uncommitted to actualizing its own mythology as the world’s foremost purveyor of liberty and individual freedom. But it sure seems committed to the mythology nonetheless.

One of the many and more infuriating ways that people try and ignore this discrepancy is to get selective about who does and doesn’t count when assessing whose life and individual freedom ought to be recognized. In some cases, the ignorance is pathological. In many others, it arises from circumstance, convenience—particularly in times of war, crisis, and disaster.

Enter Important Groups. This chapbook-length poem rips open that dynamic through the prism of the current genocide in Gaza, also weaving in disparate pieces of the American psyche like events such as 9/11 and the Kent State shooting, as well as media like Titanic and Law & Order. Because when bombs are falling, when the ship is sinking, when the National Guard has been called, whose humanity is recognized as precious? Whose death is recognized as a tragedy? And what is the function of these distinctions for the systems of power that choose to put forth these questions?

Reading this had me delving into these questions, and then at some point I was also inspired to watch Titanic for what I think was the first time since you had to watch the last half hour on a second VHS tape.

before 9/11

the audience often got reassured

that history was meaningful

because it had led to us

The American condition of feeling safe because you’re the protagonist in the last hours before disaster. To feel worthy and alive, like the king of the world, before there aren’t enough lifeboats for the lower classes. Before the dresser doesn’t have enough room for you.

The task of living through this or any historical moment is to resist any narrative that seeks to create harmony out of violence, both structural and physical, out of genocide, oppression, breathtaking inhumanity. These narratives exist to serve the powerful and not the masses, not you or me. And so what I appreciate about this chapbook is how it seeks out the antinarrative in these atrocities, examines the disharmony.

who will sort so-called

combatants from civilians dismembered

beneath the rubble

To truly believe in our own shared humanity, it is necessary to mourn all of the dismembered bodies which will be found and remain unfound beneath the rubble.

On Demonstration Forest by Kelly Clare

Near the demonstration forest, you may observe something that resembles organic growth and the conditions under which life can flourish, but don’t be fooled. Step inside to see the wiring.

In this construct that Kelly Clare has devised, technology is a site for growth, as in: a personal computer might get sprayed with a garden hose (“Like so what, motherboard”) and then on the very next page we’re presented with the image of a moldy screen. This thing is filled with such lines where nature reclaims the mechanical (“fluorescent signal receptors, pollen pouring from the modem.”), but then also where the technological spawns new forms of nature “Every computer spits out woods like it. / Poplar and pine split down into bytes.”

Of course, the first thing anyone is bound to notice when they look at this chapbook is how it quite literally reshapes the technology of written verse itself, with the book in the shape of a triangle; and lines running wildly in all directions across the page, like vines scaling a brick wall. It’s something that mimics chaotic outgrowth, but is likely to have been carefully composed.

The shape and form of this poem also works to remind you of the physical vessel which contains it each time flip or rotate the page in order to catch the next line. It exists within a construct, a controlled setting built to contain free-roaming thoughts and direct their flow.

I don’t think AI is ever mentioned once in the text, but in 2026 it obviously comes to mind when engaging with a work like this, which presents “demonstrations” as these digital imitations of life and expression, where perspective is culled from data rather than experience. “I came from the lands of fields of opportunity / Wherein a digital tractor demonstrates belaboring.” And for all the doomsday hype about AI apocalypses and robot takeovers, I wouldn’t hold your breath that this technology will ever do anything so exciting. No, the scariest thing about AI is just how boring it wants to make everything. The dorks have decided that the most urgent project of our present day is to alleviate people of their own imaginations. “The future is sitting in a mold.”

On Study for Swimming Hole by Maxwell Gontarek

In the late 19th century, German mathematician Georg Cantor set forth the argument that there are two different levels of infinity. The first is the one we most often think of, made up of “natural” numbers (i.e. 1, 2, 3, etc.) counted ad nauseum into oblivion. The other, less often considered, is the one made up of “real” numbers (the numbers represented by decimals) which can exist in infinite combinations and lengths between 0 and 1, and by extension exist infinitely between any “natural” numbers.

Study for Swimming Hole is a book with an eye towards both of these infinities. It gazes beyond the furthest event horizons of our perceptions. And it also tries to break perceptions apart into as many little pieces as it can. Here images and ideas and pieces of text will swirl and combine, and then just as soon crash against one another to burst open.

And this is where you will find life in these poems: in the gaps, in the debris they leave behind.

Another departure brought to consciousness

with its irregular framework

and its immaterial dome of calms

In the center the dawn of all

At the loss of its curve

Alternating in color

in the content of displacement

without a theme

Throughout the psychedelic mess presented by these pages, a shape is formed in its empty spaces. Momentum is built from its misdirection, its many frictions. “The content of displacement,” as if this is the speech and these are the words that language itself has displaced. Reading this book, I found so many pockets in which to get lost, to lose myself in, so many words that made me go grab a dictionary.

Until now, I’ve never really considered that there’s likely an etymological similarity between the words “collage” and “collision.” A disparate wreck of pictures, fueled by motion, loaded with reactions. The composite is less important than the interplay and the energy that it generates. I feel like I could read this book over and over and continue to discover newer, more granular infinities. I could keep finding newer and even smaller moments in which to catch my breath.

On Deadheading by Jon Conley

This is a book of death and rebirth. It’s a book where plants and insects in both natural and manicured environments come alive in its dead pages through the sheer kinesis of verse. Many of these poems are built from plain observations, arranged into music and rhythms that recreate the energy of their settings.

American pokeweed berries

Droop to insect suck

Pollinators weigh bulbs

Around & round pods

Dried of black honey

Locust, locust leaves

Sapling, many trodden

Trod, return, receive

Slipping in and out of rhyme, empty space; moving between locales where wildlife can flourish relatively untouched, like the forest, to where it grows in the cracks of human constructs, like the courtyard or the cemetery. These poems sit, they wait, and most of all they’re present in their surroundings, open to experiences both meditative and philosophical.

At the center of this book, flowers die and their titular dead heads fall to nourish a new generation. “Those who plop in the topsoil of the pot / To alone wither in their basin, such is / Their natal-bound nature.”

By the end, in a pair of sky poems, this decidedly earthbound work turns to look towards the Celestia. The verse becomes more abstract, more slippery and aloof. It’s as if, with the night sky as the backdrop, the eyes through which we’ve been observing the world, the eyes that have been wide open throughout, are finally beginning to shutter and drift off towards sleep for a new day’s rebirth.

..

Jon Conley, Author of Deadheading

On Icewalker & Dirtworm by Eric Wallgren

January 10, 10:48 AM EST

can i text u my write up right here?

January 10, 10:52 AM EST

ofc Icewalker walks

ofc Icewalker wants to melt the earth

who knew they had this relationship

cocaine—marijuana

movement to combat boredom

movement to stay alive (movement as “away from”)

boredom=death

Ice & Dirt are the repeating pattern

a consideration of spaces through which to move, a study of the media of movement

vehicle as definition

i am cold—after all that dancing

what is up is up, what is down, down

..

Hilary Plum, Author of Important Groups

On Study for Swimming Hole by Maxwell Gontarek

“This is just a really good book of poetry.” Read the rest here.

∩

Kelly Clare is the author of Demonstration Forest. Maxwell Gontarek is the author of Study for Swimming Hole. Eric Wallgren is the author of Icewalker & Dirtworm. Jon Conley is the author of Deadheading. Hilary Plum is the author of Important Groups. Published by Community Mausoleum.